Responsibilities in Public Art

25/01/2007

This is the text of a presentation I made for the "City Revitalization Seminar" at the Higher School of Humanities and Journalism (now known as the Collegium Da Vinci), Poznan, in January 2007 following the ‘Re:Generacja/ Re:Generation” exhibition. The text was simultaneously presented in Polish by the co-curator and exhibitor, Katarzyna Kujawska-Murphy.

My first experience of exhibiting a work in public proved to be an interesting one.

I found a stone on a pavement in Sródka that seemed to me to be at the very centre of the district. So, developing a theme I had used in earlier work, I built a tubular cage around the stone and chained it shut with a lock. It was a gesture made to suggest that we sometimes fail to see and preserve the interesting things and spaces around us that we no longer see through over-familiarity.

However, after a few days this is how my work looked.

Everything that was not fixed to the ground had been stolen. Well, at least they didn't take the stone! I realised that the problem is not that the public must respect artworks in public, or indeed have a respect for all public spaces as part of everyone's civic duty. The problem is of course the responsibility that the artist has to the public.

A work presented in a public space is doing something to that space. it creates a focus for social dialogue, and has an intensity of impact that often work in a gallery cannot produce. We choose to enter a gallery or museum, and in this way we set up the expectation in ourselves that we will be seeing something called 'art'. Artworks in public deny us the choice of whether we wish to see them or not. The responsibility of the artist is to work with this essential difference, and not place their personal considerations above those of the space of the artwork.

An example of how things can go wrong when an artist is not sensitive to the needs of the public and its space can be seen in the story of Richard Serra's Tilted Arc.

This work was for the Federal Plaza in New York and build in 1981. By this stage in his career Serra had started to make very large public works, and this piece is no exception at 36 metres in length and over three and a half metres in height. it cut the plaza neatly into two discrete halves, and whilst it presented an interesting sculptural intervention into space, it immediately started a controversy about the use of that particular space.

Serra had been selected by a three-member panel consisting of two museum directors and an art critic, and the design had been checked by the commissioning organisation the General Services Administration for its environmental impact, effect on pedestrian traffic, maintenance needs as well as its appropriateness for the site before it was approved for construction. But nobody considered whether the people who used the plaza actually wanted this sculpture, and the result was that it was almost universally loathed. A nearby building had a questionnaire in its lobby asking people what they wanted done with the sculpture. Of the 2662 people who responded, 166 wanted it to stay, and 2496 wanted its removal. After many years of ugly public debate and, it must be said, political manipulation, the work was eventually removed in 1989. Serra continued to try and prevent this until the very end, claiming that the government was abusing his freedom of expression as an artist, and that its removal was pure censorship.

I have no comment about the quality of the work; my point is that it was eventually considered inappropriate for the space and was then destroyed. As public art it was a failure. Richard Serra had failed to respond to the people whose space it was, and instead considered his own artistic integrity more important and used the space as a giant gallery or personal playground.

Of course I am not suggesting that the public must be consulted before making any decision with a public space. Direct democracy of this kind is impractical and can often stifle real innovation. Besides, representational democracy was developed in order to avoid this problem. But it is a delicate balance, and the needs and expectations of the public must play a part in the development of a public space. And artists have an extra responsibility here. I believe architects and municipal planners can often lose touch with their constituents, and this leaves a gap between the authorities and the public that can be filled by the intermediary of the artist. By taking on this position during a commission, the artist can help both parties by identifying the public for the work, and developing a dialogue between the two groups. This may sound too political a position for some, but I contend that public art is qualitatively different to gallery or museum art, and therefore requires a different approach.

One problem with public art is that the initial impact of a work can be lost in time with over familiarity. We pass by the monuments of forgotten generals and saints every day without a second glance. The artwork has become the furniture of the street, or worse, like a decoration that we only notice when it is no longer there. This was my motivation for highlighting the strange rock in the middle of Sródka. One way of avoiding this fate is by making public art temporary rather than a permanent fixture.

In London there is an on-going programme of public art that uses the empty plinth in Trafalgar Square to present new public works by major contemporary British artists*. Surrounding Nelson's Column are four plinths, one on each corner of the square, and each one has a typical cast statue in the monumental style so beloved of the Victorians. All except the fourth. This plinth was originally designed by Sir Charles Barry and built in 1841 to display an equestrian statue, but the government didn't release the money to make the work and so for over 150 years the plinth remained curiously empty. A few years ago, after some successful individual works were installed temporarily, the council decided to abandon the idea of a permanent statue and continue the programme of temporary artworks.

I personally prefer this option because it has certain advantages over permanent public art. By being temporary, artwork can periodically stimulate a public debate about the work and its placing, and can keep a space feeling fresh and not forgotten. If some people do not like the work, they know that in several weeks or months something else will have taken its place. And it can create civic pride and a shared sense of ownership in a space.

Artists working in public spaces have unique privileges and responsibilities that require sensitivity to the needs of the space in question, and a diminution of the usual artistic ego. By working with civic planners and exploring the requirements of the public whose space they are about to change, artists can make a contribution to the understanding of art, the appreciation of public spaces and develop the potential for a sense of community that all public spaces can create.

*the Fourth Plinth programme is for both British and international artists. Click on this link for more information:

www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/shorthand/fourth_plinth/

Caged Rock

I found a stone on a pavement in Sródka that seemed to me to be at the very centre of the district. So, developing a theme I had used in earlier work, I built a tubular cage around the stone and chained it shut with a lock. It was a gesture made to suggest that we sometimes fail to see and preserve the interesting things and spaces around us that we no longer see through over-familiarity.

However, after a few days this is how my work looked.

Bare rock

Everything that was not fixed to the ground had been stolen. Well, at least they didn't take the stone! I realised that the problem is not that the public must respect artworks in public, or indeed have a respect for all public spaces as part of everyone's civic duty. The problem is of course the responsibility that the artist has to the public.

A work presented in a public space is doing something to that space. it creates a focus for social dialogue, and has an intensity of impact that often work in a gallery cannot produce. We choose to enter a gallery or museum, and in this way we set up the expectation in ourselves that we will be seeing something called 'art'. Artworks in public deny us the choice of whether we wish to see them or not. The responsibility of the artist is to work with this essential difference, and not place their personal considerations above those of the space of the artwork.

An example of how things can go wrong when an artist is not sensitive to the needs of the public and its space can be seen in the story of Richard Serra's Tilted Arc.

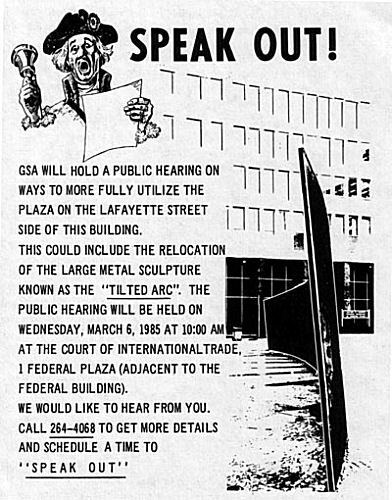

Tilted Arc by Richard Serra

This work was for the Federal Plaza in New York and build in 1981. By this stage in his career Serra had started to make very large public works, and this piece is no exception at 36 metres in length and over three and a half metres in height. it cut the plaza neatly into two discrete halves, and whilst it presented an interesting sculptural intervention into space, it immediately started a controversy about the use of that particular space.

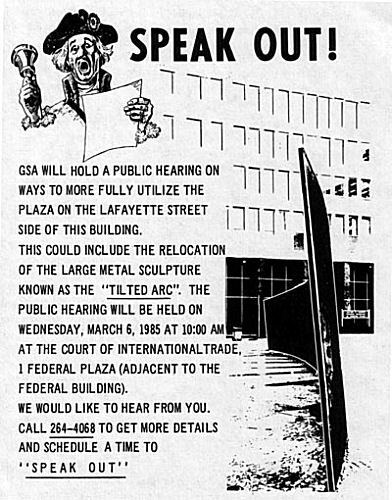

Tilted Arc demonstration leaflet

Serra had been selected by a three-member panel consisting of two museum directors and an art critic, and the design had been checked by the commissioning organisation the General Services Administration for its environmental impact, effect on pedestrian traffic, maintenance needs as well as its appropriateness for the site before it was approved for construction. But nobody considered whether the people who used the plaza actually wanted this sculpture, and the result was that it was almost universally loathed. A nearby building had a questionnaire in its lobby asking people what they wanted done with the sculpture. Of the 2662 people who responded, 166 wanted it to stay, and 2496 wanted its removal. After many years of ugly public debate and, it must be said, political manipulation, the work was eventually removed in 1989. Serra continued to try and prevent this until the very end, claiming that the government was abusing his freedom of expression as an artist, and that its removal was pure censorship.

I have no comment about the quality of the work; my point is that it was eventually considered inappropriate for the space and was then destroyed. As public art it was a failure. Richard Serra had failed to respond to the people whose space it was, and instead considered his own artistic integrity more important and used the space as a giant gallery or personal playground.

Of course I am not suggesting that the public must be consulted before making any decision with a public space. Direct democracy of this kind is impractical and can often stifle real innovation. Besides, representational democracy was developed in order to avoid this problem. But it is a delicate balance, and the needs and expectations of the public must play a part in the development of a public space. And artists have an extra responsibility here. I believe architects and municipal planners can often lose touch with their constituents, and this leaves a gap between the authorities and the public that can be filled by the intermediary of the artist. By taking on this position during a commission, the artist can help both parties by identifying the public for the work, and developing a dialogue between the two groups. This may sound too political a position for some, but I contend that public art is qualitatively different to gallery or museum art, and therefore requires a different approach.

One problem with public art is that the initial impact of a work can be lost in time with over familiarity. We pass by the monuments of forgotten generals and saints every day without a second glance. The artwork has become the furniture of the street, or worse, like a decoration that we only notice when it is no longer there. This was my motivation for highlighting the strange rock in the middle of Sródka. One way of avoiding this fate is by making public art temporary rather than a permanent fixture.

In London there is an on-going programme of public art that uses the empty plinth in Trafalgar Square to present new public works by major contemporary British artists*. Surrounding Nelson's Column are four plinths, one on each corner of the square, and each one has a typical cast statue in the monumental style so beloved of the Victorians. All except the fourth. This plinth was originally designed by Sir Charles Barry and built in 1841 to display an equestrian statue, but the government didn't release the money to make the work and so for over 150 years the plinth remained curiously empty. A few years ago, after some successful individual works were installed temporarily, the council decided to abandon the idea of a permanent statue and continue the programme of temporary artworks.

Ecce Homo by Mark Wallinger

Untitled (Trafalgar Square Plinth) by Rachel Whiteread

Alison Lapper Pregnant by Marc Quinn

I personally prefer this option because it has certain advantages over permanent public art. By being temporary, artwork can periodically stimulate a public debate about the work and its placing, and can keep a space feeling fresh and not forgotten. If some people do not like the work, they know that in several weeks or months something else will have taken its place. And it can create civic pride and a shared sense of ownership in a space.

Artists working in public spaces have unique privileges and responsibilities that require sensitivity to the needs of the space in question, and a diminution of the usual artistic ego. By working with civic planners and exploring the requirements of the public whose space they are about to change, artists can make a contribution to the understanding of art, the appreciation of public spaces and develop the potential for a sense of community that all public spaces can create.

*the Fourth Plinth programme is for both British and international artists. Click on this link for more information:

www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/shorthand/fourth_plinth/

Comments (click to expand)